Lyceum Clubs in the United States

The Lyceum Movement in the United States was an early form of organized adult education based on Aristotle’s Lyceum in Ancient Greece. Lyceums flourished, particularly in small towns in the northeastern and mid-western U.S., during the mid-19th century, and some continued until the early 20th century. Hundreds of informal associations were established for the purpose of improving the social, intellectual, and moral fabric of society.

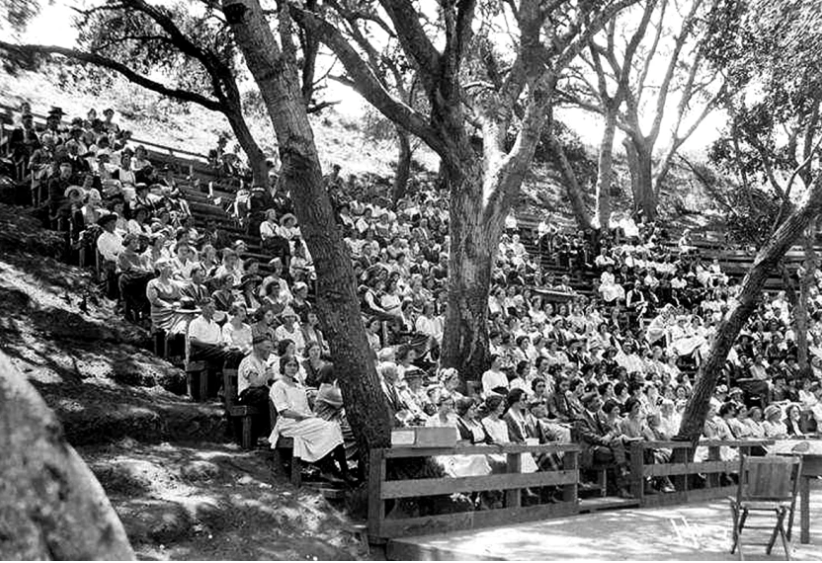

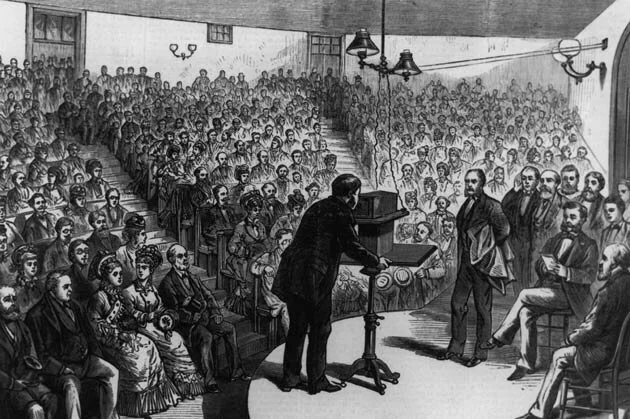

Professional speakers would tour from town to town, lecturing on history, politics, art, and cultural topics, and often holding open discussion after the lecture. The lectures were usually held in a theater or gymnasium, and sometimes in large tents, often adjacent to or part of the Town Hall. The lectures, dramatic performances, classes, and debates contributed significantly to the education of the adult American in the 19th century and provided a platform for the dissemination of culture and ideas.

The first American lyceum, “Millsbury Branch, Number 1 of the American Lyceum,” was founded in 1826 by Josiah Holbrook, a traveling lecturer and teacher who believed that education was a lifelong experience. The Lyceum Movement reached the peak of its popularity in the antebellum (pre-Civil War) era. Public lyceums were organized as far south as Florida and as far west as Detroit. Transcendentalists such as Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau endorsed the movement and lectured at many local lyceums.

After the American Civil War, lyceums were increasingly used as venues for traveling entertainers, such as vaudeville and minstrel shows. However, they continued to play an important role in the development of political ideas, such as women’s suffrage, and in exposing the public to culture and literature. Well-known public figures such as Susan B. Anthony, Mark Twain, and William Lloyd Garrison all spoke at lyceums in the late nineteenth century. The function of lyceums was gradually incorporated into the Chautauqua movement.

“We come from all the divisions and classes of society…to teach and to be taught in our turn. While we mingle together in these pursuits, we shall to know each other more intimately; we shall remove many of the prejudices which ignorance or partial acquaintance with each other had fostered…in the parties and sects into which we are divided, we sometimes learn to love our brother at the expense of him whom we do not in so many respects regard as a brother…we return to our homes and firesides from the Lyceum with kindlier feelings toward one another, because we have learned to know one another better.

”